Robert Johnson is one of the most exhibited and collected painters in Western North Carolina. At age 76, he says he’s at peace with a grim health prognosis. He recently talked with BPR's Matt Peiken about his path as an artist—from the psychedelia of 1960s San Francisco to landscapes around the world and back to the mountains outside his door.

Robert Johnson has eased himself down the shallow steps of his back deck, into an open field and onto a plastic chair.

The wind whips against the microphone Johnson’s wearing as he points out the botany surrounding the home he shares with his wife, Forrest, about an hour northeast of Asheville, in the Yancey County community of Celo. He and a previous wife first moved to Celo in 1972.

“I have blood cancer and I don’t have much longer to live,” he said. “Right now, I’m fine if I’m just sitting down, but just walking between here and the porch, I get out of breath, I start feeling dizzy, like I might faint. It’s attacked my gut and my kidneys, too. They’re giving me between two months and a year to live, so now I’m working with hospice. I mean, life is great. What could be better than sitting here talking with you?”

That outlook—turning to the brighter side by default—is the bedrock of Johnson’s life. But it took him until his 40s to lean into that outlook as an artist.

“My midlife crisis was happening at that point,” he recalled. “I wasn’t selling anything, I wasn’t getting recognition, and I was thinking ‘Maybe I’m in the wrong business.’”

In discussing his early years in art, Johnson draws a zigzag path from right brain to left brain, from East Coast intellectualism to West Coast, drug-fueled funk art to what he calls improvisational doodles.

“The doodle work, my goal, especially after reading Carl Jung, (was) that if I could go deep enough into the unconscious that way, I would get to some type of archetypal level that would be universal,” he said. “Now I feel I never got there.”

None of it found traction with the public. Johnson had already lived in Celo many years when the mountains right outside his door inspired him to paint bright, utopic, surrealist landscapes. In these paintings, still tethered in spirit to the psychedelic art of the ‘60s and ‘70s, Johnson righted a career going nowhere into one that has taken him around the world.

Johnson has traveled to New Mexico and New Zealand, Nepal and Nova Scotia, Cuba and Costa Rica; Panama to the Pacific Northwest, Italy, India and Indonesia. Their national parks have informed his art since the late 1980s.

“When I was doing these doodle works, I was looking inside myself for these images. After a while, it felt like I was staring at my navel,” he said. “Connecting with the natural world connects me with something much bigger than myself, and that’s the real satisfaction I get out of it.”

Nature informs his work rather than dictates it. Johnson paints with colors not quite found in those settings, and his shapes for mountains and trees are more interpretations than representations. Johnson also strives for a flatness of surface and agrees the components of his paintings can look like puzzle pieces.

Response to this artwork validated him like nothing he’d ever done. John Cram, founder of Asheville’s Blue Spiral Gallery, gave him his first solo show nearly 30 years ago.

“He started selling them for $500 apiece and, by the end of the show, they were selling for $1,200,” Johnson said with a chuckle. “The whole show sold out. It was like ‘Whoa!’ Totally blew me away.”

Buoyed by that confidence, Johnson applied for and received a string of grants allowing him to travel up to three months every year to gather material for new series of paintings. Cram flew Johnson to New Zealand to create a new body of work, which Cram showed with pride at Blue Spiral to New Zealand’s ambassador to the United States.

“I stopped applying for grants because I didn’t have to anymore, because they all sold out, and I had enough money to pay for my next trip,” he said. “Other people need the grant more than I do.”

Johnson pins his pronounced artistic shift, in part, on Celo and the surrounding mountains.

Contrasting the heady minimalism of his early adulthood on the East Coast and the drug-infused art he made on the West Coast, Johnson found himself in Celo drawing and painting his sense of wonderment with nature. The evolution was gradual, but it proved profound and permanent.

“I’m not really trying to make art. I’m really just trying to express my experience of what I know and what I love out in nature,” Johnson said. “I don’t really relate to contemporary art much, and I don’t even relate to artists that much. I really relate to botanists and naturalists. We have a whole lot more to talk about than other artists.”

That realization stripped Johnson’s sense of ego or concern about making work relevant to the wider art world. The irony is Johnson’s attraction to buyers only came after he no longer cared to chase them.

“I was always sort of on the edge of the art world. I mean, if you look at Art in America, my work doesn’t look like anything (in there),” he said. “The audience for that kind of work is sort of the art connoisseur, which is kind of this small group of people that sort of dictates what you should or shouldn’t like, so why even bother catering to them?”

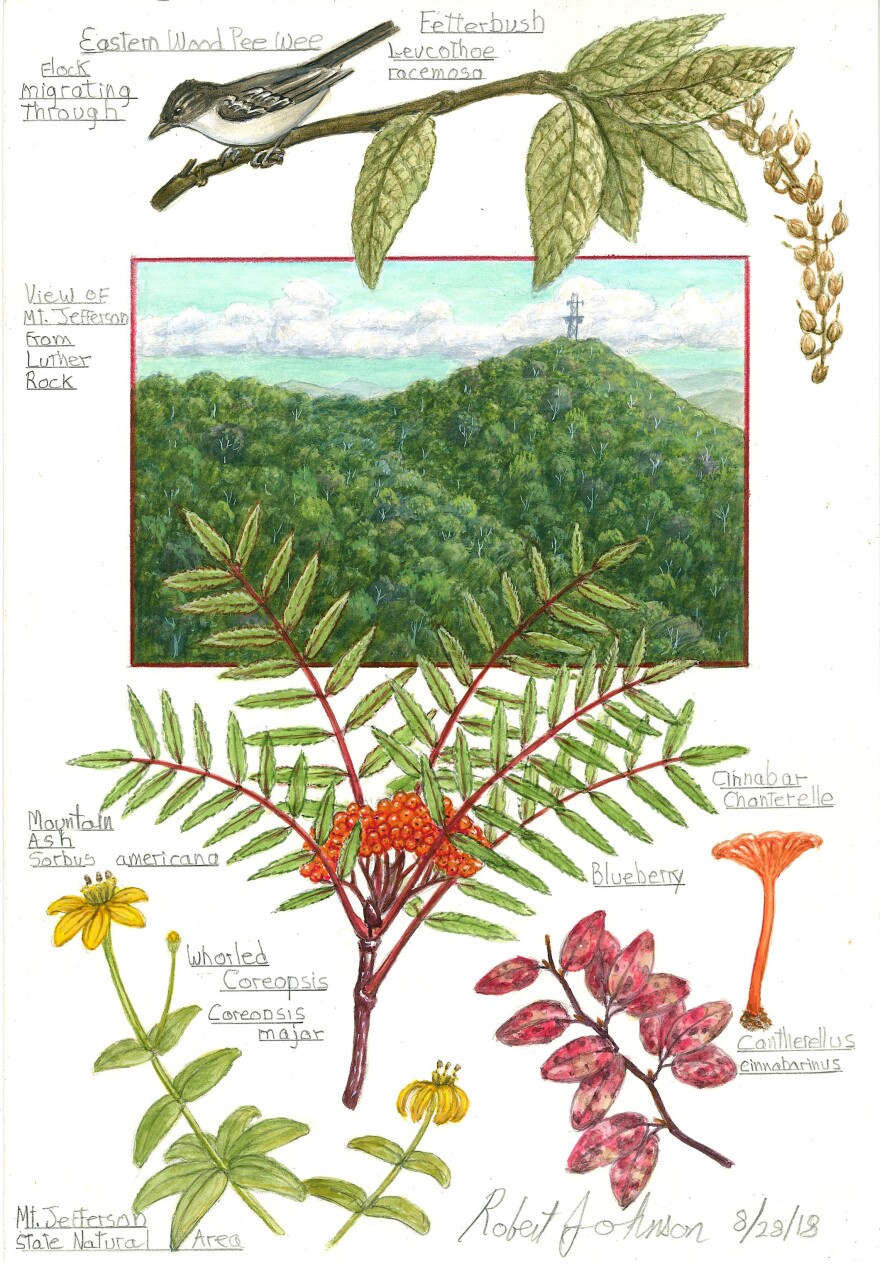

Before he paints bluebirds, butterflies, streams, a mountainside or a grove of trees, Johnson often takes photos of them along with extensive notes or sketches from the field. But when he returns to his studio, it’s as if he puts all that aside and paints what that nature evokes within him.

“Drawing on the right side of the brain, you’re copying what you’re seeing. And what I try to do, and what I think makes much more interesting drawings, you also draw what you know,” he said. “Drawing what you’re seeing and drawing what you know are two different things.”

For decades now, Johnson has trusted the maps of his soul to guide his way, artistically and otherwise. When his wife at the time, who was a weaver, discovered Celo through a class at Penland School of Craft, Johnson knew they had found the hippie enclave they had long sought.

“I think that was the happiest time of my life were those first few years when we were in Celo,” he recalled of the early- to mid-1970s. “It was like ‘Oh, we found paradise,’ and it’s still paradise. It’s my soul’s home base.”

Just as Covid-19 began its spread in the United States, Johnson received a diagnosis of terminal blood cancer. He briefly attempted and then withdrew from chemotherapy in the fall. When we spoke in mid-November, distanced on plastic chairs outside his home, Johnson said doctors had given him anywhere from a couple months to a year to live.

“When I got this prognosis, I did a lot of cleaning out to lighten my load, to get ready for dying,” he said without a hint of emotion. “I had eight boxes of journals from the 1980s to today and I just dumped ‘em all out.”

Johnson spent the past three years preparing what he sees as the largest exhibition of his career, born from visits to each of North Carolina’s 42 state parks. He said he has about 80 works from this series, which premieres in February at the Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington and comes to Asheville’s Blue Spiral gallery in the fall.

“I don’t feel like I really have any unfinished business that I want to take care of, so I’m glad this show’s all ready,” he said. “I can move and don’t feel I need to hang around to finish this show.”

Still, his desire to paint hasn’t ebbed. He’s just doing it closer to home. Two of his four children live nearby—a daughter, Cedar, in Celo and another daughter, Willow, in Asheville. A few weeks after this conversation, Johnson emailed some upbeat health news to friends and family. He closed the note by writing: “It feels like I might be around a little longer than I had thought.”

“This fall, when there were fall colors out, I’d drive down, find a place I could park the car, just sit in the park and draw and record the colors and come back and make a painting,” he said in this conversation. “I’m thinking of myself as being retired. In other words, I’m not producing paintings to sell. I’m just doing it because what else am I gonna do?—It’s all I know to do—and just enjoying it.”