The complex identity of Southern Appalachia pervades film, literature and academia, but the stereotypes portrayed in those disciplines even extend to the region’s best-known export – music – and its most famous instrument.

Even for people who haven’t seen 'Deliverance' – or waded into the literary and academic debates bubbling just beneath its surface – the twangy strains of the movie’s most identifiable symbol can be just as misunderstood.

“When I hear the opening chord of Dueling Banjos from the film Deliverance, I don't necessarily think of something. I feel something. And that feeling is, I cringe,” says IBMA-nominated Rolling Stone correspondent and Smoky Mountain News A&E Editor Garret K. Woodward.

Woodward logs more than 30,000 miles a year seeing five or six shows a week, upwards of 500 bands a year, throughout Southern Appalachia. He’s also written a book on bluegrass and knows all about the effect the movie had on the region’s musical community.

“Although it did bring a lot of exposure and publicity to Western North Carolina and East Tennessee, I also think that it did an injustice by not actually showcasing how incredibly intricate and intelligent and beautiful old-time mountain and traditional music is,” said Woodward.

The banjo’s always been a big part of that.

“So in terms of the banjo, there are three styles of banjo,” he said. There's the classic Earl Scruggs style, and then there's the Don Reno style, and then there's Western North Carolina, Haywood County, Maggie Valley's finest, Raymond Fairchild.”

Born in Cherokee in 1939, Fairchild still runs the Maggie Valley Opry, and often plays there and at the distillery down the street. Since the 1970s he’s been a world-famous banjo picker and made a number of appearances at the Grand Ole Opry.

“A lot of people says they knees is a-shakin, they’s nervous – it didn’t bother me a bit more than stepping out here,” said Fairchild. “When you play the Grand Ole Opry in this type music we play, that’s the highest you’re going to go.”

Fairchild is also a member of Bill Monroe's Bluegrass Hall of Fame, and has two gold records.

“Every time I pick it up I learn something,” he said. “And I’ve been at it 65 years.”

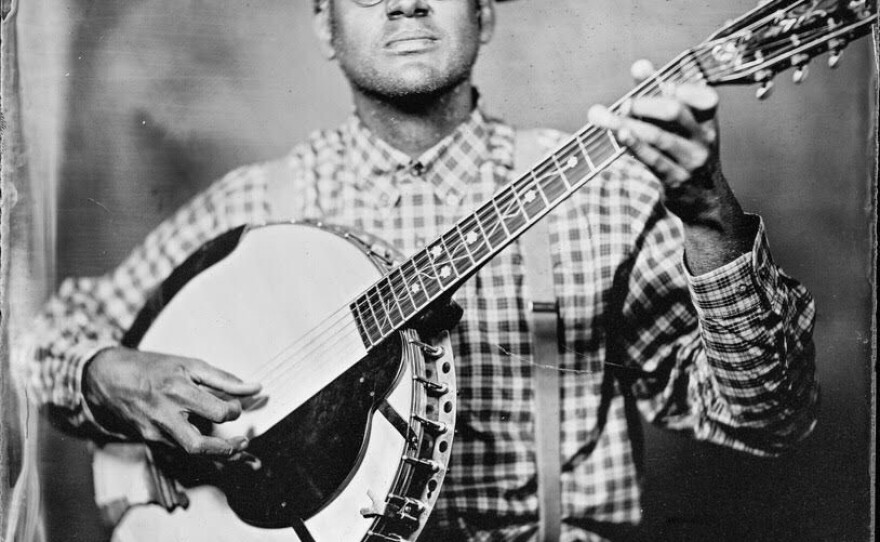

Pickers like Fairchild and Scruggs helped set the mold for what an Appalachian musician was supposed to look like, and supposed to sound like, but in reality they were building on a tradition that spanned centuries and continents, says fellow Opry alum, Grammy Award-winning American songster Dom Flemons.

“If we think about the Banjo as being an African instrument, that's, that's is the root,” said Flemons. “And we have a history and folklore that show that the Banjo was based somewhere around West Africa.”

Introduced to North America during the slave trade, the banjo was quickly synthesized into existing Scotch, Irish, English and Germanic cultures of Southern Appalachia.

Its African roots were largely overshadowed until the 1960s folk revival prompted a reexamination of the instrument that in turn spawned events like the Black Banjo Gathering, held in the mountains of Western North Carolina.

“Once I went to the gathering, I met Rhiannon Giddens, and later on I met Justin Robinson. And I happened to get a copy of a movie called Louie Bluey, which featured a musician named Howard Armstrong,” he said. “We decided to name ourselves in tribute to Howard Armstrong's band, the Tennessee Chocolate Drops, by calling ourselves the Carolina Chocolate Drops.”

Flemons left the Drops in 2013, but like Giddens and her most recent project Our Native Daughters, he’s continued to advance the discussion of what an Appalachian musician looks like, and sounds like, today.

“To know that there is a historical precedent for African Americans and any other type of person to be involved, just to be able to break the stereotype that a banjo player has to be a white banjo player was a goal for me, a personal goal for me, to try to break that stereotype,” said Flemons. “And so when we did the group, I really drove that message.”

Woodward says he hears the message Flemons and Fairchild have been preaching at shows hundreds of times each year.

“You have a room full of strangers, from all walks of life, ideologies, backgrounds, religions, whatever. That is something that is missing in our society right now,” said Woodward. “And I think that that's where the hunger and the thirst for these genres has come full circle is because people want to feel human again. And these genres and these musicians represent the essence of the human spirit and condition.”

So on that deeper level, the way the Southern Appalachian identity is portrayed through film, literature academia and especially music suggests that often the stereotypes that divide, aren’t as strong as the ties that unite.

“Exploring Southern Appalachia” is a Blue Ridge Public Radio series on how the 1972 Burt Reynolds’ film “Deliverance” touched Southern Appalachia. This series will explore the film’s mark on literature, whitewater, music, academia and the cultural identity of the region as a whole.