The Cherokee language is officially in a state of emergency. The number of fluent speakers has been dwindling for years. BPR spoke with Cherokee language experts about what is being done to teach and preserve their native tongue.

There are only about 200 fluent Cherokee speakers left in the Eastern Band of the Cherokee(EBCI) and only about 2,000 nationwide. Leaders in the Eastern Band say that’s not because the language isn’t being taught - but rather a lack of teachers and Cherokee families speaking the language at home.

Fluent speaker Laura Pinnix sits in the Cherokee Cultural Center at the Cherokee Central Schools surrounded by supplies for a basket weaving class. She’s director of the program. She’s been teaching for about 40 years and remembers having conversations about language preservation in the 1970s.

“As far as the state of emergency in this time and age, it is very important, I think for me it's always been a state of emergency,” says Pinnix, who's a member of EBCI.

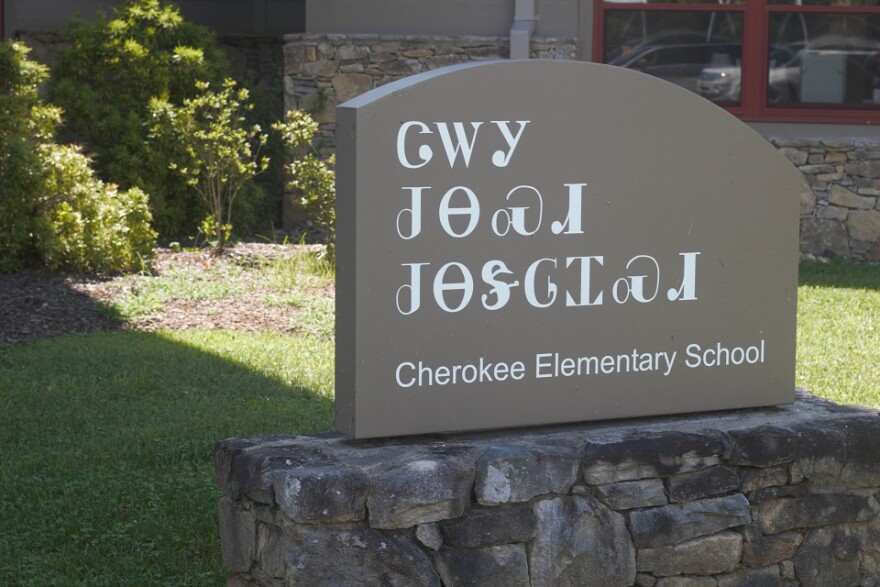

Cherokee has been taught at schools on the Qualla Boundary in some capacity since at least the early 1980’s. Officially, even in Cherokee schools, it’s considered a foreign language credit. It’s the only native language with that distinction in North Carolina. Western Carolina University offers a degree in Cherokee Studies and language classes. The tribe also has online resources such as a dictionary and a language learning app.

Kayleen Rockwood is 24. She goes by “Cree.” She has a degree in Anthropology with a minor in Cherokee from Western Carolina. Rockwood says that she has been learning Cherokee since she was about 13 years old and is now at about 40% fluency.

A lot of people I know say their grandparents didn’t really speak it to us because they were scared from what happened to them in the boarding school so a lot didn’t teach it because they thought it wasn’t necessary,”says Rockwood. She grew up speaking Cree.

She’s Eastern Band of Cherokee and Plains Cree from Canada. Rockwood works at the Western Carolina University Cherokee Center. The Center was founded in the 1970s to connect the Cherokee people to the University.

Cherokee Elder JC Wachacha is 69. He is a fluent speaker who helps out at the New Kituwah Academy which was founded in 2004. He remembers what it was like to switch to an English school.

“I went to Cherokee school in 6th grade and then went to public school after that and I had a hard time because I didn’t have a good fluency in English - I still don’t, explains Wachacha.

The reality that many elders were encouraged not to speak Cherokee in school or punished for not speaking English is one of the reasons that it’s not spoken as frequently.

Bo Lossiah introduces himself in Cherokee and in English.

“Hello, My name is Bo Lossaih I work here at New Kituwah Academy. I’m the curriculum instruction and community supervisor here.”

When Lossiah started at the Academy in 2009, the infants who had grown up learning Cherokee at the school were starting kindergarten. There will be just under 100 students enrolled in the fall.

The plan was to educate students as Cherokee first language speakers from pre-k to sixth grade. When the school started there were about 400 fluent speakers in the Eastern Band and 8 full time fluent teachers. But Lossiah says that as the student’s got older, there were fewer teachers and looming end of year tests in English to graduate to the next grade.

“It wasn’t an easy sell. So we started integrating English. That was poison to the system,” says Lossiah. “The students learn some Enlish throughout the day but mostly still speak Cherokee.”

That is the gap between living in an English world while trying to teach Cherokee says, Lossiah. Now there are just three full time fluent speakers teaching. The school is constantly working to develop curriculum for describing concepts like jet propulsion into Cherokee.

That’s where translator Myrtle Driver Johnson comes in. She’s 75-years-old and has been translating for over 40 years. She's also considered a Beloved Woman in the EBCI.

“We should have been producing fluent speakers long ago,” says Johnson, who also teaches Cherokee.

Johnson only speaks Cherokee to her 6 month old grandson in hopes that he will become fluent. She remembers his first word one day when the family was sitting outside on the porch.

“He saw that butterfly go by and said, ‘Ka-Ma-Ma’ and my daughter thought he said Mama. But I said, ‘no’ he said ‘kamama’ - butterfly,” says Driver.

These educators hope that the state of emergency will inspire tribal members to start learning the language. As first speakers age, Rockwood says it’s time for second language learners to take more responsibility.

“We need to get out there with our elders and communicate with them and learn from them. If we lose the old ways then we are basically lost,” says Rockwood. She is starting a two-year adult Cherokee immersion program in August.

Officials from the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes – the other two are in Oklahoma - plan to share resources and work together more to revitalize the language.