Ask any addict and they’ll tell you, coming off of opiates can be a hellish ordeal.

“Opiate withdrawal is the most painful experience I’ve ever had in my life.”

“Imagine the flu a thousand times worse.”

“Bone marrow throbbing inside of the bones.”

And if you ask them what an opiate high is like?

“A warm hug from God. It’s just like you’re floating in a sea of… Awesome.”

“Peaceful and serene.”

“A warm, fuzzy blanket that coats your whole body.”

It’s the reason recovery from opioids is so difficult for addicts like these, most of whom have asked to remain anonymous. They can either choose the euphoria of getting high, or the anguish of coming down. So for many of them, it’s a no-brainer, and the opioid abuse continues, often with deadly consequences.

In March, the Center for Disease Control declared that opioid abuse is now an epidemic, estimating that overdose claimed the lives of more than 28,000 people in 2014—more than any year on record. To combat this, the CDC established new guidelines for physicians treating patients for pain.

Additionally, the drug naloxone has been distributed to law enforcement agencies, emergency rooms and outreach programs across the nation, as an antidote for opioid overdose. So far these efforts are working, say drug counselors—especially in areas like Western North Carolina, where opioid abuse has become particularly pervasive. In a small commercial space alongside U.S. 441, just a few miles south of Franklin, recovery specialist Stephanie Almeida and a small group of volunteers are huddled around a table assembling overdose reversal kits that include naloxone, because opioids are becoming just as popular here as they are anywhere else in the state.

“You can’t get a better drug,” says Almeida. “I mean it removes all of the physical pain, it removes all of the emotional pain.”

Almeida is the founder of Full Circle Recovery Center in Macon County—a non-profit outreach program that counsels locals through their addictions, and works to prevent drug overdoses.

“In my experience, people use substances, sometimes to have fun, but a lot of times when we’re using opiates and drugs in that family, it’s because there’s some sort of pain.”

Almeida who began working as a substance abuse counselor in Boston in the late nineties, says that opioid abuse is nothing new, yet the public’s effort to properly combat it, is.

“My first overdose death was a young man in Somerville High School who was playing hockey; he was at a party and he took an oxycontin pill and a beer and he overdosed, and he passed away. I’ve been working with this for almost two decades already, and it’s taken this long for the stigma to be reduced enough for folks to actually be talking about it.”

After losing count at nineteen of the amount of deaths by either suicide or drug overdose, Almeida moved to Western North Carolina in 2007, but would eventually come to continue her work in substance abuse prevention.

“I moved here to heal, you know?” she explains. “I figured [there were] more trees than people, and a kind community, maybe [I would] get involved with prevention work here, and maybe stop the problem from happening—but that wasn’t the case.”

While the communities proved to be kinder, and the trees more plentiful, Almeida also came to find a drug culture all its own upon moving to the mountains—where the people were both proud and conservative, lived small towns — where everybody knew everything about everyone else, and tended to handle their problems quietly, and on their own.

“I think there’s a lot of denial in the south about drug use. The information just wasn’t really available in the same way that we had it. There was a substance abuse task force that was meeting to talk about things. But I think there was a lot of denial back then. Now we can’t deny it. I mean, we’re losing people every day.”

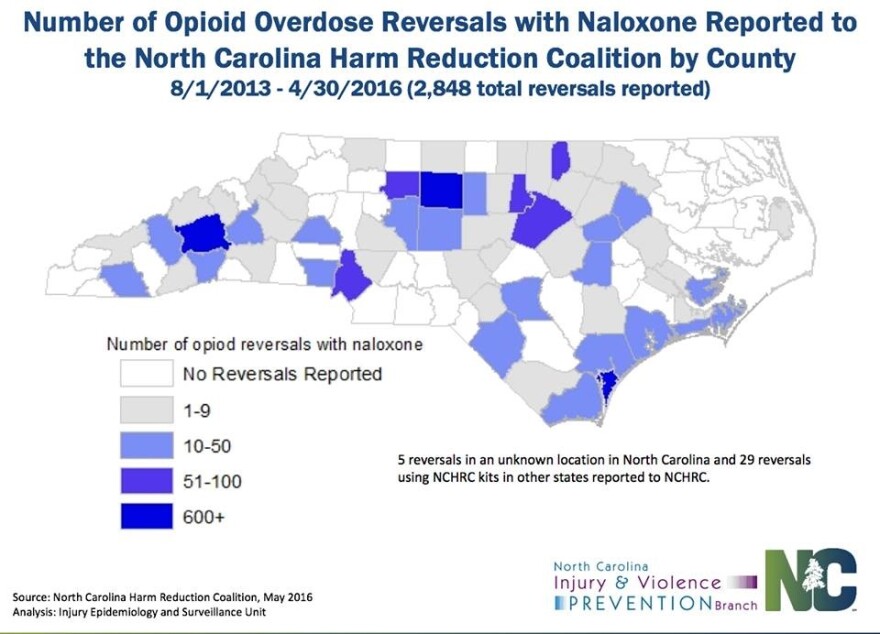

The death toll from heroin alone has spiked drastically in recent years. Back in March, the North Carolina Department of Health reported that heroin-related overdoses had increased by nearly six hundred percent since 2010—an increase which has even shaken the state’s smaller mountain communities in the west during that same period. For instance, thirteen of Buncombe County’s seventeen recorded overdoses occurred in 2014. To combat these statistics, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition began distributing overdose reversal kits which include naloxone—an effective antidote for overdose which, to date, has been administered more than 3,400 times throughout the state in the last three years.

Today it seems that the opioid epidemic has spread its way deep enough into North Carolina society, that it’s become as contentious a matter among policymakers in Raleigh, as it is in the seclusion of the Smoky Mountains.

“Opioid abuse, both heroin and prescription drugs, is a killer” That’s North Carolina Attorney General Roy Cooper, during his recent gubernatorial debate with Governor Pat McCrory. “Over a thousand people a year in North Carolina are losing their lives, even more across the country than in automobile accidents with accidental overdoses.”

And McCrory: “In my very first State of State speech, I brought up the terrible problem of addiction and also mental health—which has been totally ignored in the state of North Carolina in the past ten years. Everyone’s pretending it didn’t exist. But it existed in families and communities throughout North Carolina. There is no discrimination when it comes to addiction or mental health issues.”

Tomorrow in part two of our series on the opioid epidemic in Western North Carolina, we’ll take a look at its impact on law enforcement in the region.