This coverage is made possible through a partnership between BPR and Grist, a nonprofit environmental media organization.

Lauren Bacchus is one of many Ashevillians who have found themselves strangely enamored with the city’s sinkholes.

She’s a member of the Asheville Sinkhole Group — an online watering hole of more than 3,400 members — where locals eagerly discuss the chasms that mysteriously emerge throughout the city. She even owns a T-shirt, emblazoned with the phrase “For the love of all things holey.”

The Facebook group recently saw renewed interest when a small pit appeared at the intersection of Swannanoa River Road and Biltmore Avenue late last month. “Oh, we’re so back,” one user wrote.

For Bacchus, the sinkholes remind her of the impermanence of manmade structures.

“I don't want to discredit that sinkholes can cause a lot of damage and hurt people, but they do evoke this feeling of excitement and curiosity and mystery,” she said. “It's a void that opens up where you thought something was solid. And that's the reality of the ground we walk on all the time.”

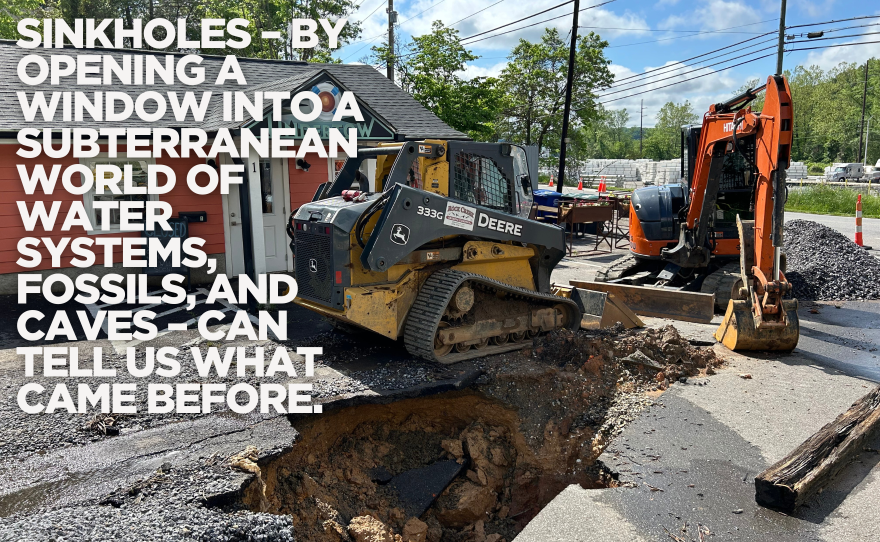

Given the flooding and busted pipes that followed Hurricane Helene, sinkholes have become a pressing problem for Asheville and much of the Appalachian region. Roads already battered by record flooding are pocked by the blemishes, which can be anywhere from a few inches to several feet in diameter (though particularly monstrous ones can reach hundreds of acres in width and hundreds of feet in depth).

A marked increase in their numbers has been keeping road crews busy, according to city officials.

“I don't want to discredit that sinkholes can cause a lot of damage and hurt people, but they do evoke this feeling of excitement and curiosity and mystery,” she said. “It's a void that opens up where you thought something was solid. And that's the reality of the ground we walk on all the time.”

“We're definitely seeing an elevated number of sinkholes since Helene. Most of the ones we've encountered have been caused by culverts that have collapsed,” Clay Chandler, the city’s water resources spokesperson, said.

Bacchus has been a member of the sinkhole group since 2019, which formed that same year that a parking lot in North Asheville hollowed into a cavity 36 feet wide and 30 feet deep. That story made national headlines. The owners of the property tried to fill in the sinkhole with concrete, unsuccessfully, before the city ultimately declared the building on site as too dangerous for occupancy. The building remained unoccupied for years while the piping that caused the sinkhole was repaired.

Over the years, Asheville has seen many dramatic sinkhole moments. Jason Sandford, a local journalist and photographer, has followed them for years as part of a project he’s dubbed the “#sinkholepatrol.” He recalled an instance in 2020, when a sinkhole opened near Gold’s Gym and threatened to swallow a truck.

“There was a tension-filled rescue as a local tow truck company worked for a couple of hours to successfully remove the truck from the jaws of the maw,” he said.

Late last year, a Waffle House in Mars Hill suffered a similar fate. The day before Hurricane Helene brought record flooding to the region, a sinkhole swallowed much of the diner’s parking lot, ultimately leading the owners to shut down the business.

Sinkholes can form in a few different ways. Much of the Appalachian region sits on porous limestone, made of the compressed shells of sea creatures that, millions of years ago, roamed shallow ancient seas. This topography, known as karst, is full of tunnels and caves. But in Western North Carolina, an area with notably no limestone, what we call sinkholes are mainly the product of human intervention – construction fill, bad plumbing, and choices made by developers and construction companies that result in water going places it shouldn’t.

The 2019 Merrimon Avenue sinkhole was caused by paving and piping over what was once a natural stream; the pipe corroded and collapsed. NCDOT said at the time that water may have flowed around and corroded the pipe.

United States Geological Survey maps paint much of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia in a bright-red high sinkhole risk zone. Sinkholes have threatened, among other things, a Corvette museum in Kentucky, police station in West Virginia, and an East Tennessee mall. For years, a sinkhole at the bottom of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Boone Dam drained it like a bathtub. They’ve also caused tragedy. A Pennsylvania grandmother died late last year after falling into one while looking for her missing cat.

They have an insatiable quality to them, often growing and growing, making the ground beneath our feet unstable. They’re difficult and sometimes impossible to repair, which can inconvenience travelers and business owners.

For many locals, though, sinkholes also present a sense of wonder and fascination – the sense that we’re peering into another time or place. In fact, sinkholes can tell us a lot about our own relationship to the environment and the natural history of our region. Sinkholes – by opening a window into a subterranean world of water systems, fossils, and caves – can tell us what came before.

And, experts say, we might see more of them after big storms like Helene as sinkhole risk increases with climate change.

Why climate change means more sinkholes

Ernst Kastning, a retired professor of geology at Radford University in Virginia, told BPR that sinkholes are often a natural reaction to a big change - like a storm. Natural sinkholes form as water moves downhill, such as via an underground cave system.

“The water has to come out somewhere,” Kastning said.

Human-caused sinkholes can force a similar reaction through artificially creating what scientists call “void space” in the ground. Void space affects how much water the soil can hold; that space can also collapse.

“If you come in there and dig something or put in something or build something or modify the water flow … you're likely to have nature react to that,” Kastning said. In particular, pumping water out of the ground and introducing asphalt– for constructing building foundations or roads, for example – causes depressions and sinkholes to form.

“The recovery time, which of course is human beings fixing everything, putting things back together, or letting nature run its course, is obviously much longer than the time it takes for the event to happen.”

After a large storm event, the land attempts to restore an equilibrium, which often means water and soil go places that are inconvenient for us. Geologists colloquially call this the earth’s “plumbing system” - the complex network of underground drainage pathways that are a part of the water cycle. Storms and human disturbance can cause abrupt changes, or slow changes that look abrupt when hollowed-out ground suddenly collapses.

“The recovery time, which of course is human beings fixing everything, putting things back together, or letting nature run its course,” Kastning said, “is obviously much longer than the time it takes for the event to happen.”

While sinkholes can be caused by a variety of factors, the main source stems from rain. Warm temperatures can also make the ground and the rock under it softer.

Sinkholes after a storm like Helene, Kastning said, are part of nature’s way of righting itself. But if big storms happen more often, so will sinkholes. “The frequency of these things is increasing,” he said.

A great place to become a fossil

On a sunny April afternoon, three scientists walked across an ancient sinkhole, now filled in and covered in grass, on the Gray Fossil Site in Gray, Tenn. Active archaeological digs are currently covered with black plastic and protected with fences.

The 4.5-acre, 144-foot deep sinkhole and surrounding forest provided water to prehistoric animals, and it also served as many of their graves. Or, as museum collections manager Matthew Inabinett put it: “When a place is a good place to live, it’s also a good place to die!”

As a result of sinkhole conditions - water and mud at the bottom, namely – scientists can now use it to peer 4.5 million years into the past. Of course, they’ve only (literally) just scraped the surface. “We've estimated a few tens of thousands of years at current rates to excavate to the bottom,” said fossil site Americorps member Shay Maden. “So we've got job security on that front for sure.”

They’ve found fossils of exciting species like giant squirrels and mastodons, but also have seen more familiar faces - rhinos (one of which the team has named Papaw, since he died at an advanced age) and tropical reptiles.

The site, Inabinett said, has become a scrying glass to understand climate conditions of the past. It can also tell us what our own climate might look like at a few degrees warmer.

Many of the fossils found so far are from a geological period called the Pliocene epoch, which was about 3 degrees Celsius warmer than today’s climate. That’s also the amount the Earth is projected to warm by 2100. Oceans were about 25 feet higher. Back then, alligators lived in Appalachia.

The region’s biodiversity, among the highest in the world, survived multiple periods of extreme heat and cold. Later, the humid climate of the Pliocene - a little warmer than our own – quickly succumbed to the Ice Age.

“I am attracted to sinkholes because of the humbling feeling they evoke. I am reminded I am a small animal on this planet, and there’s more going on below the surface than we may realize.”

Because silt flows toward the ocean, the Appalachian region has few easily accessible fossils, meaning this sinkhole - the Gray Fossil Site - is our main window into the ancient past of this region.

“The Southern Appalachians are one of the most biodiverse regions in North America,” Inabinett said. “To study this time period, the early Pliocene, is really useful for understanding how that diversity originated.”

While not every sinkhole can offer a portal into prehistoric times, they do tap into something primal. For Bacchus, who goes on regular walks to check new and growing sinkholes, sinkholes represent the concept of “the void” and bring an opportunity for people to reflect on concepts bigger than themselves.

“I am attracted to sinkholes because of the humbling feeling they evoke,” she said. “I am reminded I am a small animal on this planet, and there’s more going on below the surface than we may realize.”