Jackson County leaders have removed a plaque – installed during the Black Lives Matter movement – that previously covered an inscription on the pedestal of “Sylva Sam,” a Confederate monument.

The plaque – which read “E pluribus Unum,” a phrase on the Great Seal of the United States that means “out of many, one” – had stood for four years as a compromise to prior calls for the Confederate soldier statue to be removed. It was removed this month without a public discussion or vote by county elected leaders – which one former commissioner has described as an act “behind closed doors.”

Sylva Sam was erected on the steps of the then-Jackson County Courthouse in 1915. Amid calls for the removal of the monument, County Commissioners between 2020 and 2021 agreed to add the “E pluribus Unum” plaque covering the original inscription that reads “Our Heroes of the Confederacy.”

Now, the Confederate heroe's message – and a Confederate flag on the statue’s base – is back.

At a recent county meeting, residents weighed in – both on the meaning of the monument and the lack of public disclosure before the compromise plaque was removed.

Jackson County resident Megan Machnik thanked commissioners for restoring the original monument.

“This monument has stood as a silent witness to generations of change, struggle, and growth. Well, it may represent different things to different people, for many of us it's a part of our heritage, an emblem of the history that has shaped our families, our town, and the South itself,” Machnik said.

“Your actions show that we do not erase our history, but we engage with it. We do not destroy what came before us, but we strive to understand it so that our children can better know where they come from and who they are.”

Local author David Joy spoke against the removal. Joy’s comments from the meeting have gone viral online with over 100,000 views across social media.

@baxterforhendo Author David Joy speaking at the Jackson County Commissioners’ meeting last week about their Confederate monument. #ncpol #rural #confederacy

♬ original sound - Gina Baxter

“I think about the black communities in Jackson County. I think about people who have descendants here who go back hundreds of years. And what every one of you who voted for that is saying is that you revere a moment in time when their ancestors were in bondage. That's what that means,” Joy said.

Joy in 2023 wrote “Those We Thought We Knew,” which is about the monument and the history of the Mt. Zion AME Church in Cullowhee. The church was founded by 11 formerly enslaved people and its building was ultimately moved by Western Carolina University, including the graveyard.

Joy said he thinks about that history in Jackson County when discussing this monument.

“A church who was forced to dig up their dead and move them to the back side of that mountain to make room for a dormitory,” Joy said. “You're saying to all of those people, people who have served this county as deputies, people who have served this county in all kinds of capacities that that's what you celebrate.”

Joy and others who were against the removal also spoke about the way in which the plaque was removed.

Jackson County Manager Kevin King confirmed that the plaque was removed by commissioners earlier this month. He said commissioners agreed to the removal over the phone in a series of individual phone calls.

This might seem like a violation of public meeting law, which states that a majority of a public body cannot meet together without it being an open public meeting.

However, Assistant Professor of Public Law and Government at the UNC School of Government Rebecca Fisher-Gabbard says it isn’t because commissioners weren’t on the phone together.

“That is technically not a violation of the open meetings law because that would not constitute a majority of the members of a public body gathering,” Gabbard said.

Gabbard also cites statute NC GA 100-2.1(a - b) that governs the protection of monuments, memorials, and works of art.

“That specific statute does not necessarily require a public hearing and or a public vote,” Gabbard said.

At least one commissioner has said publicly that he didn’t agree with the decision – but without minutes or an official vote, it's unclear how consensus was reached.

Former Jackson County Commissioner Gayle Woody was on the board when the decision to keep the statue and add the plaques was made. She says she was “very disheartened” that this decision was made without public input.

“The thing that hurt me the most was it was done behind closed doors, which was the opposite of what our county commissioners did at that time,” Woody said.

We opened it up to the community, not everyone was happy with us. and we still were respectful and we made our decision based on all the different viewpoints.”

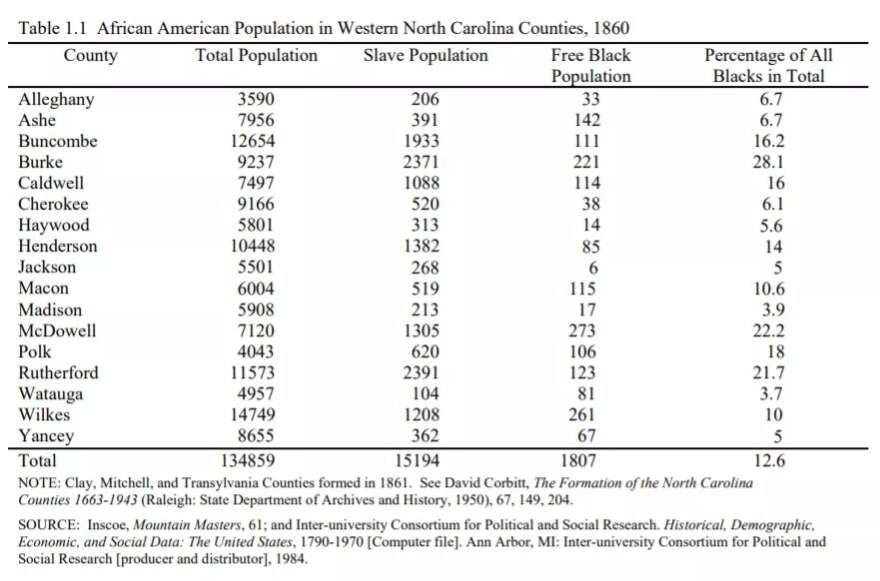

In light of the Confederate inscription’s return, Jackson County resident Teri Cole-Smith proposed more historical context to be added to the monument, including the number of people who were enslaved in Jackson County in 1860.

“A statue that glorifies the Confederate soldiers as heroes doesn’t just memorialize history. That would be done with information that contextualizes, not glorifies,” Cole-Smith said.

According to historical census records, there were 268 Black people enslaved as well as six free Black people in 1860. This represented 5% of the county.

Cole-Smith also read the names of 30 families in the county who were listed as enslavers during the meeting. The census lists: Enloe, Fisher Cockerham, Norton, Hill, Hooper, Coward, Allen, Davis, Brown, McKiney, Rogers, Rice, Zachery, Sloan, Hackett, Whitmire, Krems, Gibbs, Hyatt, Mingus, Hyatt, Coleman, Crawford, Wilson, Bryson, Rogers, Thomas, Love, Cook. Some families include multiple members listed.

A brief history of the ‘compromise’ plaque

In July 2020, Sylva Town Council voted to remove the monument known as Sylva Sam, BPR reported. The original meeting for the vote had to be rescheduled after the meeting was “Zoom-bombed” with hate speech including the N-word. However, the town does not have the power to remove the monument because it is on county property.

In August 2020, Jackson County Commissioners decided not to remove the monument of a Confederate soldier in downtown Sylva known as Sylva Sam. The decision came after months of protests and the night of the vote was no different.

Two groups were formed around the issue: Jackson County Unity Coalition, which was against the removal; and Reconcile Sylva, which was for removal. Both groups are now inactive.

After nine months of discussion and public protests, the “compromise plaque” stating “E Pluribus Unum” was approved and added to the monument for $14,000 in May 2021.

The protests also sparked discussions about weapons at demonstrations and online threats. At least one misdemeanor assault charge was filed by a Reconcile member.

A brief history of the ‘Sylva Sam’ monument

The monument in “commemoration of the deeds of the Confederate soldiers and their wives, both living and dead” was originally unveiled in 1915. Jackson County residents, local businesses and a few people from Atlanta and Tennessee paid for the monument. This included A.C. Reynolds, Sylva Supply Co. Hooper Drug Co., and more.

James H. Cathay, Chairman of the Monument Association, presented the monument, and Hon. Baxter C. Jones, a member of the General Assembly from Jackson County, accepted Sylva Sam, on behalf of the county. The dedication mentioned that eight companies of Confederate soldiers from Jackson County served in the Civil War.

This monument was built to honor the 164 soldiers from Jackson County who served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, and all the citizens who helped with the war effort.

Between 33,000 and 35,000 North Carolinians in the Confederate Army died in battle, of wounds, or of disease between 1861 and 1865, according to the state encyclopedia website.

The orators for the occasion were Hon. Corsey C. Buchanan and Gen. Julian S. Carr. Carr is well-known as the speaker at the unveiling of “Silent Sam,” the Confederate monument at UNC-Chapel Hill, which was removed in 2019. Carr ultimately did not attend the Sylva unveiling and General Theodore F. Davidson of Asheville took his place.

Here's the Jackson County Journal from 1914-1915 sharing the news about the monument. Courtesy of the WCU Special Collections Library.

Sylva’s monument was rededicated on May 11, 1996 to honor Jackson County Veterans of all wars. Speakers at the event included Joe P. Rhinehart, president of Jackson County Historical Association; Clyde Bumgarner Post Commander of the William E. Dillard Post 104 at American Legion, Sylva and Chairman of Statue Fund Phillip Haire.

The monument was also restored for this event and the program lists donations from about 100 families and businesses.

Newspaper articles from the Sylva Herald in 1996 show the tone of the event.

“In 1915, when this statue was first dedicated, the people of Jackson County had worked hard to rebuild their region. They had a new county seat, a new courthouse and a growing town. This statue exemplifies that period in time - 1915. It was a testimony to a separated nation now reunited …,” Joe Rhinehart, former president of the Jackson County Historical Association, said. “That is why we are here, 80 years later. As work continues on the restoration of this courthouse, we continue to give thanks that we are a united nation, reconciled and reunited both physically, spiritually and, as such, we strive to honor the past but live for the future.”