A few years ago, Tom Karches' teenage son was suffering from a severe earache. It was late in the evening and the emergency room was the only option.

"They brought him in and they did a strep test," Karches said. "They gave him a couple different pills... And then they sent us on our way."

Most people can probably guess what came next.

"And then about a week later, I got the bill for $3,000," Karches said.

The bulk of that bill was simply for setting foot in the Emergency Department. Karches says he's aware of the facility fee. But even so, it seemed an exorbitant bill for an earache.

"I just thought it was kind of ridiculous, considering what we had been there for and what we had done," he said.

In North Carolina, state Treasurer Dale Folwell has focused increasing scrutiny on health care systems, and hospitals specifically. He's become fond of repeating a phrase: "In the United States, we do not consume health care. Health care consumes us."

The treasurer's office oversees the State Health Plan, the health insurance plan that covers 740,000 state employees and dependents that paid out $3.8 billion in total net claims last fiscal year.

Folwell says health insurers and the pharmaceutical and medical device industries have received fair criticism for their part in the country's more than $3.5 trillion health care bill. But he says hospitals are just as much to blame for what he calls one of the biggest wealth transfers of his lifetime.

"A transfer of wealth especially from lower and fixed income people to these big multibillion dollar corporations who disguise themselves as nonprofits," Folwell says.

In the last year, the Treasurer's office has produced four reports critical of different aspects of hospital finances. One argues that nonprofit hospitals receive major tax exemptions but don't hold up their end of the bargain in the implicit social contract. They do provide charity care, and are quick to tout those figures, but communities pay for that charity care through the tax subsidies.

"We give you the subsidy, and you do good things for the community. You help people," said Ge Bai, a Johns Hopkins University professor of accounting and health policy who has reported extensively on nonprofit hospitals.

The subsidies are substantial.

In Wake County alone, local governments miss out on nearly $15 million per year in property taxes they would collect from Rex, Duke Raleigh, WakeMed and other hospital facilities. Plus, these health systems are exempt from state and federal taxes, and can raise money through tax free bonds.

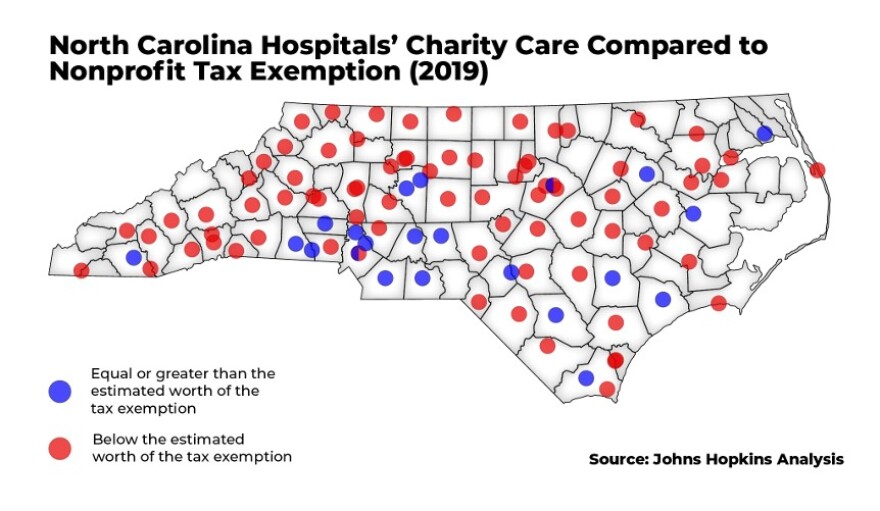

Collectively, North Carolina's nonprofit hospitals received tax breaks of more than $1.8 billion, according to the treasurer's office report with analysis from Johns Hopkins University. Yet fewer than 25 hospitals provided enough charity care to offset those breaks.

"Nonprofit hospitals have to do more," Bai said. "Some of them are doing a great job, but many have to do more to deserve taxpayers' trust and subsidies."

Health economists are increasingly viewing the term "nonprofit hospital" with skepticism. During the pandemic and with the help of COVID-relief money, North Carolina's seven large hospital systems saw their cash and investments grow by $7 billion, according to an analysis of hospital financial records by the treasurer's office. They recorded net income — a figure that includes investment returns — of more than $5 billion in 2021 alone.

Rice University Chair in Health Economics Vivian Ho says hospitals should prioritize care for the uninsured, especially in a state like North Carolina that has not expanded Medicaid.

"We've got large numbers of uninsured patients and these not for profits should be looking after them rather than earning, to me, what seems to be excess profits," she said.

Hospitals have pushed back against the treasurer's reports, saying they "have used misinformation and half-truths and that make inaccurate conclusions," according to the NC Healthcare Association, the group that represents hospitals. The group says blame for high costs rests with other parts of the health care system like health insurers, not the people who have made careers of providing health care.

"The reality of the current situation in North Carolina is that a majority of hospitals have negative operating margins this year and that both Medicaid and Medicare reimburse hospitals for caring for patients below the actual costs of providing that care," according to NCHA. "We are seeing more hospitals laying off staff because of their financial situations. Our emergency departments are overcrowded with patients and running out of bed space. Patients with behavioral health needs are staying in hospitals for weeks because there is nowhere for them to go for advanced treatment."

Steve Lawler, the association's president, says blame rests with other parts of the health care system like health insurers, not the people who have made careers of providing health care.

"Sometimes people blame the provider community for the fact that they've got a health plan that requires the first $7,000 or $10,000 to come out of their pocket," Lawler said. "And most people have a really difficult time dealing with that."

Lawler acknowledges it’s true that patients with private health insurance pay more for care than the actual costs. But he says hospitals need this extra revenue because they provide care to people who can’t afford to pay.

"We've got a health system from a financing perspective that, whether we like it or not, there's a social compact between those of us who have insurance and those who don't to help be part of the solution for those who are uninsured to cover their care," he said.

Ho says there is plenty of blame to go around. But that hospitals need to take their share.

"I think health economists realize this," she said. "The reason why our health insurance premiums are increasing is because hospital prices have risen so quickly. And to me it's the greatest tax on the middle income American."

Duke University Health Economist Barak Richman says there are certain specifics within the reports he disagrees with, but the overall tone is correct.

"Most of our health care dollars go to hospitals right now. Most of that money is subject to what I guess you could call overcharging, monopoly prices," Richman said. "We're spending on services that are not necessarily high value. There are much better ways to spend our money. And the hospitals by and large have not been politically accountable."

There's a couple of reasons for this, Richman said. For one, hospitals are in the business of making people healthy. So, they benefit generally from a positive social perception. They are also big employers, and so they historically get some cover from the business community.

"The chamber of commerce and other entities come to their defense," he said. "Whereas really they should be directing their ire at the hospitals for consuming so many resources that could otherwise go to education or tax breaks for business development and the like. And are really not returning benefits either economically or health wise."

Richman and other economists say the tide winds are changing, in part because businesses are spending so much money to offer their employees' health insurance. Governments, too, are starting to ask more critical questions of hospitals to check that patients are getting good value for their money.

One barrier to sweeping reform is simply economics. Society needs hospitals, and hospitals need revenue. Patients are the paying customers who provide that revenue.

But economists say there are ways to reward health systems that keep populations healthy, instead of only treating them when sick. Adding more urgent care facilities, or paying bonuses for care that prevents a hospitalization, should be given more emphasis. Benefits managers at companies of all sizes should demand more health insurance options, giving employees the choice to have less insurance coverage for lower premiums.

And finally, nonprofit hospitals should be more transparent. They play an important role in society, but also receive significant benefits for that role. They should create annual reports that accurate juxtapose their full tax benefit with the charity care they provide. Then let the public decide if that's a good deal.