Southern Appalachian identity is complex and loosely defined. But when it is, the portrayals are often unflattering. From whitewashing to stereotyping, the region is not all about poor hillbillies.

Blue Ridge Public Radio followed the debate through film, literature, academia and music to learn more. In this installment we look at the echo of the film “Deliverance” across the region, from art and whitewater to the lasting stereotypes.

Burt Reynolds and the 1972 film "Deliverance" have had a lasting impact on Southern Appalachia beyond the iconic movie. But the portrayals of that fateful river run haven’t always been accurate or beneficial.

You hear those famous few chords that define the film. For many those notes evoke a pig squeal.

For Haywood County resident Herbert “Cowboy” Coward they are nostalgic. They remind him of his friend Burt Reynolds who died last year.

“He was a real good friend to me. He called me and stuff over the years. We stayed in contact with each other. That’s what you call nice and a good friend you know,” says Coward.

Coward played the “Toothless Man” in "Deliverance". You probably recognize his famous line:

“You sure have got a pretty mouth boy,” says Coward in the film. Almost 40 years later Coward will still say those famous lines anytime.

“Fall down on your knees town feller if you’ve ever done any praying you better pray now.”

Getting that iconic role is a story in itself. Coward met Reynolds while he was working as a gunfighter at the old west amusement park Ghost Town in Maggie Valley. From there Reynolds recommended he be cast in the film “Deliverance.” Coward remembers his audition well:

“So Burt told me when I got over there that the director, he’ll ask you to act like you’re mad, act like you’re hurt, and he said when he asks you to act as mad as you can act, he said you just do whatever falls into your mind,” says Cowboy. "So when he did I just smacked him good. And he said, you’ve got the part. So that’s how I ended up in the movie Deliverance you know.

Coward is proud of his role in the film. Despite the fact that he can’t read he’s been in three films and is a local legend in Southern Appalachia.

You can hear his squirrel Angel start chattering. He tells him, “You better mind me or gonna get a whoopin’.”

He’s the man with the pet squirrels. When we visited him, we also met his other two squirrels Amos and Andy. He tells Angel:

“I’ve got the only squirrel that goes to church every Sunday over at Longs Chapel. You’re the only animal that does that, ain’t you boy?”

Many others don’t share Coward’s enthusiasm for “Deliverance.” The negative stereotypes of Appalachians as illiterate shine runners still persist today.

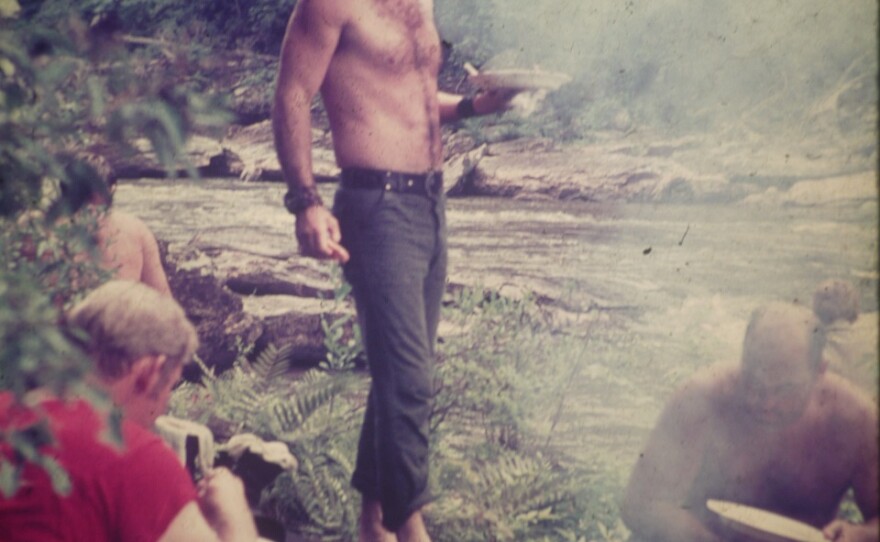

Doug Woodward, who lives in Macon County, is still angry about the way the film portrayed the people along the Chattooga River and in Clayton, Georgia where some of the film was shot. He worked as a stuntman and consultant for the canoeing in the film.

“It’s understandable that the people of Rabun County weren’t happy with the way the film came out,” explains Woodward.

“But once you're running the river - whether you are in a kayak or a raft - you are in absolutely wild county. I won’t say 'Deliverance country.' That probably should be deemphasised. There are a lot of people who haven’t been to the South who think, ‘oooh I wouldn’t want to go near where those things happened on the river.’ But that’s not the South.”

In 1972, canoeing made a splash with thefirst slalom event at the Olympics in Munich. Whitewater sports boomed following the film’s release, as amateurs flocked to the river. Quite a few people died but soon the professional rafting industry was born. Woodward’s own rafting company Southeastern Expeditions was started in 1972 after he bought three rafts from the film crew with his friend Claude Terry.

Payson Kennedy was a consultant and stunt man with Woodward in the “Deliverance.” His life was changed after the film.

Kennedy met with BPR at his home on the Nantahala Outdoor Center property. The house sits on the old Nantahala River bed next to a waterfall. Kennedy and his wife helped found NOC starting in 1972 with Horace Holden. In 1973, they moved their family up from Atlanta to Swain County.

“The first summer that we were here we lost money - only grossed $45,000 dollars and we showed a loss,” says Kennedy. “But after that first summer I was just so caught up in being in the flow state and in being out on the river.”

He says their first summer, all the employees were Boy Scouts and Georgia Tech students.

Outdoor recreation has since become a multi-billion dollar industry pulling in over $28 billion just in North Carolina. Nantahala Outdoor Center is one of the largest outdoor recreation companies in the nation.

Kennedy has his own doubts about the way “Deliverance” portrayed Appalachians.

But he’s glad the film highlighted the Chattooga river- because it helped preserve it.

“The Chattooga is my absolutely favorite trip. It’s a Wild and Scenic River so there is almost no development to speak of along it. The river bank is actually in better respects now in some places than when I started paddling,” says Kennedy.

Wild and Scenic is a protected designation signed into law in 1968. President Jimmy Carter added the Chattooga River to the list. Carter canoed on the river with Woodard back in the 1970s. Then-Governor Carter was actually a part of the first team to ever go over Bull Sluice Rapid in an open canoe.

Ripples of the impact of the movie “Deliverance” are still felt across Southern Appalachia.

But before it was a movie, it was a book by a former U.S. poet laureate that - like other works before it - helped to perpetuate the mythical stereotypes of the mountains.

“Exploring Southern Appalachia” is a Blue Ridge Public Radio series on how the 1972 Burt Reynolds’ film “Deliverance” touched Southern Appalachia. This series will explore the film’s mark on literature, whitewater, music, academia and the cultural identity of the region as a whole.

Nantahala Outdoors Center is a sponsor of Blue Ridge Public Radio.